Triangulations of products of triangulations

11th of April, 2018

At a conference this week, I ended up having a conversation with Nicolas Vichery and Eduard Balzin about why simplices are the prevalent choice of geometric shape for higher structure, as opposed to e.g. cubes or globes.

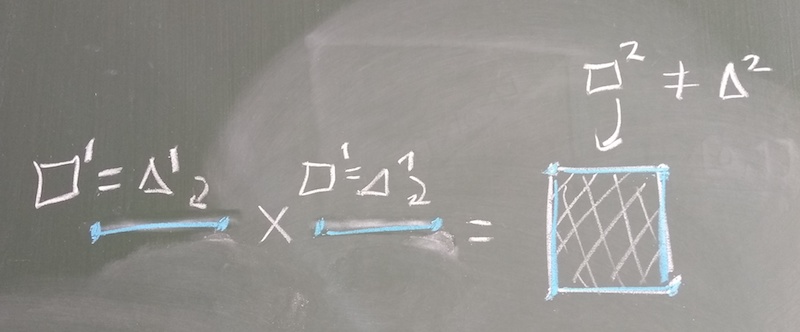

I know there are a bunch of nice properties that simplices have that other shapes don’t have1, and they seem to be the natural choice when you start thinking about higher categories as quasi-categories and filling of horns etc., but I always thought that simplices were badly behaved with respect to taking products.2 Nicolas, however, showed me a great little calculation that solves this problem. Neither I nor some of the other people I spoke to had seen this before, so I thought it would be worth spreading the word.

If we take the (geometric realisation of the) 1-cube (the interval [0,1]), then we can take the product with itself to get [0,1]\times[0,1], which is automatically the 2-cube. More generally, any product of cubes will itself be a cube. For simplices, however, this is not at all immediate: think of the problem of trying to find a triangulation for a product of spaces when calculating simplicial homology in an undergraduate course, for example. Explicitly, if we take the product of the (geometric realisations of) two 1-simplices (the interval [0,1] again), then we, as above, get the space [0,1]\times[0,1], which is not a \Delta-complex (in the language of Hatcher). To triangulate this space, we need to add a 1-simplex along the diagonal of the square.

This isn’t too hard to see, but for arbitrary triangulations of spaces, it’s much harder to see what extra simplices we need to add to their product to recover a triangulation. Even if we can figure out how to do it for hard examples, then we still would need a way to describe an algorithm for doing it to any product space. But there is a ‘trick’, which works as follows: write your simplices as simplicial sets, including degeneracies3, and then take the product in the category of simplicial sets.

Consider our example of \Delta^1\times\Delta^1, i.e. [0,1]\times[0,1]. Define the simplicial set X_\bullet by

\begin{aligned} X_0 &= \{[0], [1]\}\\ X_1 &= \{[0,0],[0,1],[1,1]\}\\ X_2 &= \{[0,0,0],[0,0,1],[0,1,1],[1,1,1]\}\\ &\vdots \end{aligned}

that is, all simplices in degree 2 and higher are degenerate (and we include all of them); the 0-simplices correspond to the points 0 and 1; and the 1-simplices correspond to the line from 0 to 1, as well as the two degenerate ‘lines’ from 0 to 0 and from 1 to 1_.

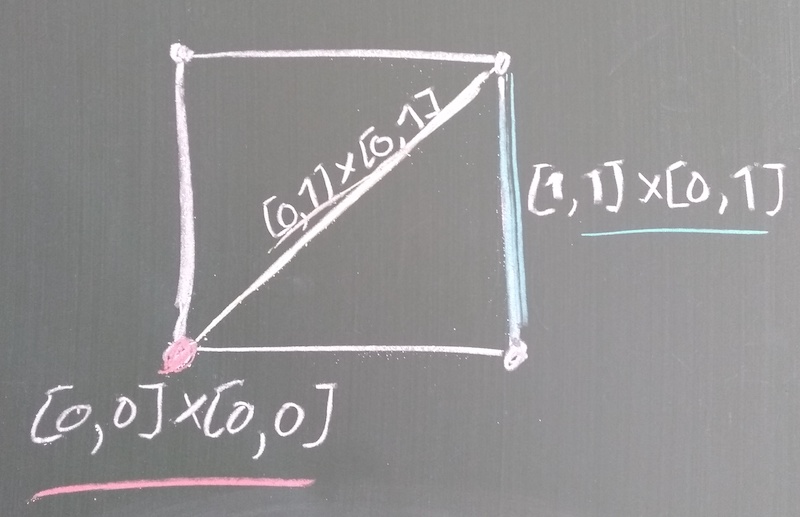

When we apply geometric realisation, these degenerate simplices will ‘vanish’, and so we can just look at what the non-degenerate 1-simplices of X_\bullet\times X_\bullet are to see what happens in terms of triangulation. There are nine 1-simplices in the product:

\begin{aligned} &[0,0]\times[0,0], \quad [0,0]\times[0,1], \quad [0,0]\times[1,1],\\ &[0,1]\times[0,0], \quad [0,1]\times[0,1], \quad [0,1]\times[1,1],\\ &[1,1]\times[0,0], \quad [1,1]\times[0,1], \quad [1,1]\times[1,1]. \end{aligned}

Five of these are non-degenerate,4 and the one that interests us is [0,1]\times[0,1]: when we apply geometric realisation, this will be a 1-simplex along the diagonal of the square.

In essence, the idea is simple, but it’s a trick that I’d never seen before, and it really makes me ‘believe’ in simplices.

Or, at least, not a priori. This is sort of exampled by the fact that the cube category is a test category that is not strict, but becomes strict when we consider cubes with connections. See (as always) the nLab page on test categories.↩︎

I mean, what follows doesn’t really answer what we were actually discussing at all (why simplices are the ‘right’ choice, if they even are), but just assuaged one of my doubts about the niceness of simplices that originally led me to wonder about this problem in the first place.↩︎

Geometrically, this means we take ‘lines’ that are actually points, ‘triangles’ that are actually lines or points, etc. Algebraically, this means that we take simplices in the image of the degeneracy maps s_i^p\colon\Delta_p\to\Delta_{p+1} given by s_i^p\colon[0,1,\ldots,p]\mapsto[0,1,\ldots,i,i,\ldots,p].↩︎

The ones not in the corners of our 3-by-3 list, i.e. those that have at least one component non-degenerate.↩︎